In a world – and a ground! – where records are broken almost every day, it is rare to come across a batting feat that has lasted 101 years. But at Trent Bridge on 25 June 1921, one of Australia’s greatest attacking batters played the innings of his life and forged records, some of which remain unchallenged.

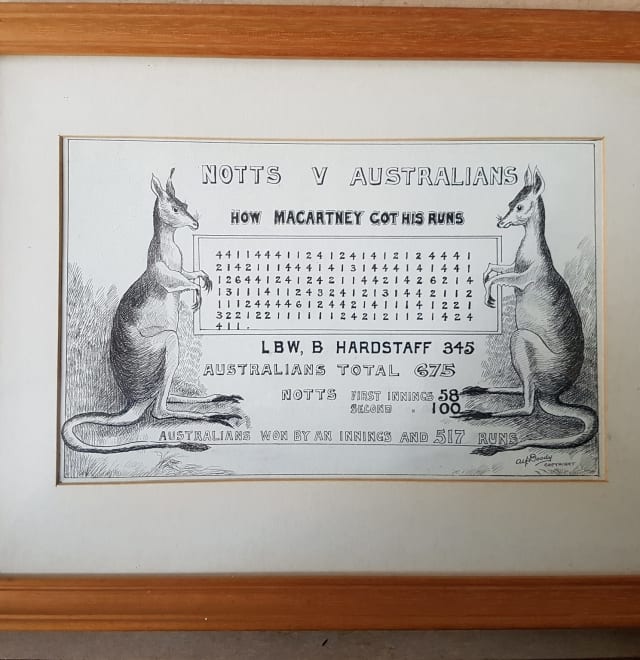

Charlie Macartney, the ‘Governor General’, playing for the touring Australians against Notts made 345 in little more than four hours – a display of aggressive intent that was, at that time, the highest score made by any Aussie for their national XI.

It remains the biggest score for an Australian in England and the highest individual score to be made at Trent Bridge.

Until a certain Brian Lara chipped in with 390 en route to another imperishable batting total, it was the most runs scored in a single-day in First-Class cricket – and it took more than 70 years for Lara to break Macartney’s record.

Macartney is the link between Trumper, flamboyant hero of cricket’s first ‘Golden Age’, and Bradman, the ultimate run-making machine – combining the flair of the one with the determination of the other. By 1921, he was something of a veteran, having first played for Australia in 1907, but was in a tremendous run of form. That record-breaking 345 came in a run of centuries in four successive matches – the others being 105 v Hampshire at Southampton, 193 v Northamptonshire at Northampton and 115 in the Ashes test England at Leeds, where he raced to three figures before lunch (an achievement as rare then as it is now).

At Trent Bridge, he took full advantage of a missed slip catch when he had scored just 9 – the normally reliable George Gunn spilling a very catchable nick – to punish an almost full-strength Notts side. In those four hours he hit four sixes and forty-seven fours, a batting display described by both the Nottingham Evening Post and the Sunday Pictorial as ‘dazzling’.

The Daily Herald called it a ‘most dashing piece of batting’ and the Daily News wrote of his ‘wonderful footwork together with extraordinary accuracy and power’; the Nottingham Journal went further and described ‘a perfect banquet of joy’ – which was especially gracious considering that he was putting the home team to the sword.

In the citation as one of the Wisden Cricketers of the Year in 1922, then editor Sydney Pardon called Macartney. “a law to himself--an individual genius, but not in any way to be copied. He constantly did things that would be quite wrong for an ordinary batsman, but by success justified all his audacities. Except Victor Trumper at his best, no Australian batsman has ever demoralised our bowlers to the same extent.”

Perhaps least impressed of all by his tremendous feat was the man himself. A number of contemporaries reported that Charlie Macartney was unconcerned by records, or totals, but simply enjoyed the challenge of batting. This is borne out by his own biography in which that historic innings gets just three or four paragraphs – and most of that is about his batting partner ‘Nip’ Pellew who figured in a stand of 291 with the ‘Governor General’.

That nick name was bestowed on Macartney by Kent and England cricketer KL (Kenneth) Hutchings during the England tour to Australia in 1907-08 at a time when Charlie was a bowling all-rounder and not yet the dominant batsman he was to become. Most commentators suggest that it was his authoritative style that earned him the soubriquet that stayed with him throughout his career. The actual Governor General of Australia at the time was Lord Northcote, who was the third such appointee and the first to really make a mark in the post. At the time of the England tour he was involved in a political dispute with the Australian Prime Minister, Alfred Deakin, and would have been much in the news when the cricketers were in the country. Hutchings presumably saw some parallel between the autocratic Northcote and the authoritative Macartney.

Charlie himself offers more light-hearted reason: “…my wife relates with glee a conversation heard by her. One small boy to another ‘why do they call Mac the ‘Governor General’? ‘Because he’s so cocky of course,’ was the reply”! He reports in his biography, My Cricketing Days*.

That cheeky approach was exemplified in his Trent Bridge knock for, having reached his double century (in only 150 minutes), he signalled to the Pavilion. Arthur Carr, Notts skipper on the day, asked if he wanted a drink but Macartney said that he wanted a heavier bat and indicated that he was going to attack. Which he duly did, adding his next 100 runs in only 48 minutes. At the time, it was the fastest triple century in First-Class cricket in terms of minutes (198). There is a small but neat representation of that innings in the Heritage Store at Trent Bridge, an acknowledgement that, even though Notts were on the receiving end, this was an innings to celebrate.

Ironically, had George Gunn held that slip catch it would have made very little difference to the outcome of the match as the Australians racked up 675 runs and the home side, no doubt demoralised by Macartney’s treatment, subsided to just 58 and 100 to lose by an innings and 517 runs, still (we’re relieved to say) the biggest defeat in the club’s history.

Charlie Macartney, born in New South Wales on 27 June 1886, played cricket until 1926 and finished with 15,019 First-Class runs (top score – unsurprisingly – that 345) at 45.78 and 419 wickets at 20.95 with a best of 7-58 against England at Headingley in July 1909. He played six times at Trent Bridge, including the match v South Africa as part of the 1912 Triangular Tournament, and in 35 Tests for Australia.

Macartney died on 9 September 1958, in Little Bay, Sydney, aged 72. Even without that memorable triple century he would have earned a place in the pantheon of great Australian batsman, as much for his style as for his figures.

Sir Jack Hobbs said that: “…we thought him a very unorthodox player, but we soon realised he was brilliant…[with] a wonderful eye. He was a charming fellow and a highly confident cricketer’.

Jack Fingleton, Australian cricketer and commentator said of him, ‘Because of his audacity, because of his all-round competence, the little ‘Governor General’ will never be forgotten.’

The 1921 scoreboard at Trent Bridge is testament to the day when the ‘Governor General’ ruled over Nottinghamshire cricket.

* A copy of My Cricket Days is in the Trent Bridge Library

June 2022